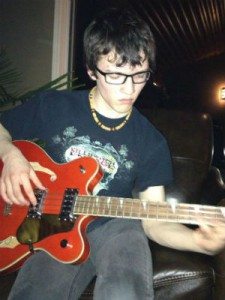

Yellowknife resident Timothy Henderson, who has died at the age of 19, touched hundreds of lives in the city, the North and beyond as an actor, musician, poet, and friend.

Parents Ian Henderson and Connie Boraski say Timothy died in an accident last week, while acting out a form of suicide scenario.

Information: Celebration of Timothy Henderson’s life on Saturday, May 2

Tributes: How friends remember Timothy Henderson

Ian, Connie, and Timothy’s stepfather, James Boraski, would like to tell Timothy’s story from their point of view. They hope publicizing what happened may help other families and young people in future.

What follows was told in their own words to Moose FM earlier this week, shortly after the decision was made to switch off Timothy’s life support.

Growing up: ‘They said they had systems in place’

Timothy Henderson had been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and Asperger syndrome. As a child in Yellowknife, Timothy received support from the NWT’s healthcare system.

Ian Henderson (Timothy’s father): The disconnect for Timothy started at 17, when he transitioned out of the pediatric healthcare program as a child. At 17 years old, you’re now treated as an adult. That’s where the big disconnect started in terms of resources.

The other big disconnect was when he hit university in Edmonton. The transition from the mental health system in the Territories to the mental health system in Alberta was basically non-existent. And then the services that we perceived were available at his university were available only on demand.

James Boraski (Timothy’s stepfather): Timothy was somebody who’s afraid to ask for help and, rather than [the university’s services] being a prescribed help, it was a latent help. ‘If you come to us, we’re there for you.’

Connie Boraski (Timothy’s mother): Timothy never wanted to be a burden to anyone. That was a real challenge for him, to ask for help.

Ian Henderson: They said they had systems in place and were very confident in handling him. I thought I was leaving him in good hands.

When we were making arrangements for him to leave [the university, earlier in 2015], they said, ‘Oh, well Timothy hasn’t approached us, so we haven’t provided any services.’ So he never went back.

The documentation and excellent reports commissioned by the Yellowknife school system were provided to them. They clearly indicated he needed monitoring, help with scheduling, help with logistics and follow-up. And obviously they didn’t do that.

The other shocking thing this lady said to me – the special needs coordinator at the university, when she learned of his troubles – is she said, ‘Oh, we have a specialist in Edmonton that’s been very effective in dealing with students with Timothy’s issues.’

The very unfortunate thing is he could have been under the care of that physician when he was down there. Because they weren’t proactive, it wasn’t identified.

James Boraski: Timothy had a number of mental health challenges. He was smarter than a lot of normal kids, but he wasn’t like somebody who had no issues, right? This kid needed some assistance and some guidance. Often times, he would take things so literally that he didn’t understand their meaning.

The obstacles that Connie and Ian faced were just… it didn’t really lend to Timothy’s best care.

Ian Henderson: My question is how often does a child in need – a scared, insecure child that does not know how to navigate the bureaucracies, that are challenging even for an adult to navigate – how often does a child need to go as far as checking himself into psych wards before somebody takes a serious interest in him, and stops dismissing him and invalidating him?

‘If you met him, it would probably take you a while’

Ian Henderson: Timothy had been diagnosed with having ADHD and Asperger’s. He was extremely high-functioning and if you met him, it would probably take you a while to figure out there were some quirks to him.

He was very literal. He would assume that he knew what you were talking about when you gave him instructions. He was so respectful and considerate that he wouldn’t come back and ask for clarification, as much as we all encouraged him to do that.

So he got a lot of instructions wrong.

Right through the school system, there were a lot of disconnects where his marks weren’t reflecting his scholastic achievements because he did not hand work in. He always did the work, but somehow he couldn’t get it handed in properly.

Connie Boraski: I’ll give you an example. Timothy was in Edmonton at school, and heading home for Christmas, back to Yellowknife on an airplane.

He was getting ready to go and I told him, ‘You need to be at the airport an hour before the flight.’ His interpretation of what I’d said, even though he’d been on many airplanes with us and flown on his own, was to leave the university – to get to the airport – an hour before the flight. You had to make sure he understood and interpreted what you said clearly.

But he was very social. His social abilities were fantastic, so he didn’t have some characteristics [of Asperger syndrome]. Unless you knew him really well, you would not know that.

Looking for help: ‘He had incredible highs and lows’

Connie Boraski: Last summer was the first time he started checking himself into the psych ward in Yellowknife.

Ian Henderson: When he was in Edmonton, he checked into the psych ward – he arrived by ambulance after a possible drug overdose. He took too much of his medication, he was concerned and the people around him were concerned, so they got an ambulance.

Connie Boraski: That happened at the end of February, or probably the beginning of March [this year].

Ian Henderson: They checked him out, and sent him home. The next weekend he was feeling like he was a danger to himself and he went back over to the hospital. They sent him home again.

Twice he reached out in Edmonton and then, when he got home to Yellowknife, he was admitted to the psych ward twice – and released twice.

James Boraski: There was once, before he’d left for school in the fall, where he had admitted himself as well.

Ian Henderson: Timothy’s big concern, and the reason he was reaching out for help, was he had these incredible highs – the best day of his life – and then, within hours, he would be having the worst day of his life.

These incredible mood swings were very hard on him. They made him very insecure and made him feel like he was at risk. That’s why he was reaching out to the medical system, to try to mitigate that.

Timothy had been cutting for a long time, on his arms, for stress release. After he was told that was not appropriate – and I suspect it was no longer effective, as well, as his mood swings were getting worse and worse – he started to play with self-sabotage. Suicide scenarios. All to do with asphyxiation.

The conclusion that we’ve come to understand started from a comment his brother made: he said, ‘Timothy is so bad at tying knots.’ And Timothy is not bad at anything. There was a reason for that.

So anyways.

Timothy’s demise happened as a result of an accident.

Something went wrong when he was acting out one of these scenarios.

Online advice: ‘He left his Facebook account open’

Ian Henderson: After I found Timothy [following the accident], I was back in the house – and we are so fortunate that Timothy left his Facebook account open on his computer.

I discovered that, because the youth of the North are not getting help from the medical system, they are self-counselling between themselves.

Timothy was counselling people as far away as Arizona on pregnancies, abortions, these kinds of things. Timothy himself was being counselled by a group of children – I say children, I mean these are young adults now, in their late teens, but they’re still in the high school system.

For instance, the last young lady that Timothy had been chatting with had twenty-eight thousand chat messages in that thread.

So that tells you the extent of the services that children are giving to each other, because they cannot get help from the medical system.

James Boraski: Not only giving to each other, but indicating the need. When we talk about counselling, we’re talking about experiential counselling. We’re not talking about trying to replace the medical system.

We’re talking about people who have reached out, either through chat groups or blogs, and they’re following these threads to people who have had these experiences, so they can try to find out how to help themselves.

Ian Henderson: The reason we’re bringing this forward publicly is to hopefully bring more resources to the individuals that Timothy has been in touch with. We’re not trying to blame these people [in the healthcare system]. We understand they are overworked and under-resourced.

We’re hoping exposure of this situation will encourage the powers-that-be – the financial powers, the political powers in Canada and the States – to make more resources available at the prevention and treatment end, and do whatever we can to stop the body count.

Health resources: ‘Frustrated, dismissed, and invalidated’

Connie Boraski: The care that Timothy has had since this whole thing [last week’s incident] has happened, both in Yellowknife and in Edmonton, has been phenomenal. It’s been just incredible.

If those resources could be made available for kids that reach out, even one time – that they don’t just pass it off, they follow through like they would with someone with a traumatic head injury – that’s what we would like to see.

Ian Henderson: The resources available to us in the past week – to medevac Timothy to Edmonton, for organ donation, the professionalism and the care made available to us as a family – have been incredible. I’m overwhelmed that that’s available.

I just wish that it didn’t need to be available, and that those resources could be equalled at the prevention and treatment end.

I don’t know how anybody could reach out more than Timothy did to get help, and be frustrated, and dismissed, and invalidated.

Connie Boraski: In Edmonton, there was not one person that wasn’t available to talk to us, to listen to us, to answer any questions. Whatever we needed, whether it be spiritual, physical, mental.

If he had had that kind of consideration at the first turn, we would not be here today.

James Boraski: And a lot of those professionals indicated their frustration that they’re left to mop up the mess that could have been prevented.

Timothy Henderson’s legacy

Ian Henderson: The legacy that’s living on is the transplantation of several of his organs, which has given several people in Edmonton a second chance at having a high-quality life.

James Boraski: You just have to look at the testimonials to see the ‘caring’, the ‘generous’, the ‘selfless’. That’s who Timothy is. He took the time out of his schedule to help everybody that he could, despite the fact that he, himself, was crying for help.

We thought that in addition to his organ donations and things like that, how else can we keep the legacy of Timothy going?

We thought it would be great to set up some kind of legacy fund or scholarship. Timothy was engaged in all the arts – acting, poetry, English – and he played at least nine instruments. We thought that, through this fund, Timothy could highlight and be giving in terms of a scholarship or some type of award.

Special needs kids would be a high priority, if they needed some help or financial assistance. This fund could be administered on an annual basis, and the legacy of Timothy Henderson live on in a fine arts scholarship of some format.

Our goal is to make sure Timothy is recognized for the exemplary work he has done in his short 19 years, and that it will perpetuate and permeate into the lives of other people that take some interest in this story.

They may have kids of similar needs who’ll benefit from all the actions Ian and Connie are undertaking now.

A service in memory of Timothy Henderson will take place at Yellowknife’s DND Gym, at the Multiplex, from 2:30pm on Saturday, May 2, 2015.

Timothy’s family hope to live-stream the service, in the hope that Timothy’s friends around the world can be a part of it.

The family asks that, in lieu of flowers, people wait for information on how to donate to a fund being established in Timothy’s name.

The NWT Help Line is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, if you need to talk.